This story was originally published on Tourism Ticker 5/08/2020

Did you ever hear about the renowned Franz Josef glacier guide, that once guided a lost troop home by sticking glow worms to his shoulder?

Or the guide from Rotorua that made international headlines when she welcomed Eleanor Roosevelt to Rotorua with a hongi?

These are the sorts of stories that provide the richness and depth to our experiences and contribute to the cultural wealth of Aotearoa New Zealand.

NZ Māori Tourism is delighted that the Government has recognised the importance of Māori tourism to the Aotearoa New Zealand economy.

While we celebrate this achievement, it is not without a reminder of the struggle that other operators and sectors are tackling.

Many sectors across the board are facing immense pressures. This should not go unacknowledged. Tourism has been hit hard and, as a result, it has been in the spotlight. Many kaimahi are also facing uncertain futures. The struggle is real and we mihi to you all.

On Saturday 1 August, the Minister of Tourism, Hon. Kelvin Davis announced Māori tourism businesses were among 126 businesses that received Strategic Tourism Assets Protection Programme (STAPP) funding.

Many of those Māori tourism businesses hold strong legacies in their communities that date back to more than 200 years.

Franz Josef Glacier Guides

In Franz Josef Glacier / Kā Roimata a Hine Hukatere (the original, Ngāi Tahu name for the Franz Josef Glaciers), the earliest recorded expedition was in 1857 when local guides took the first Europeans over the glacier. Sadly, the names of these guides were not recorded.

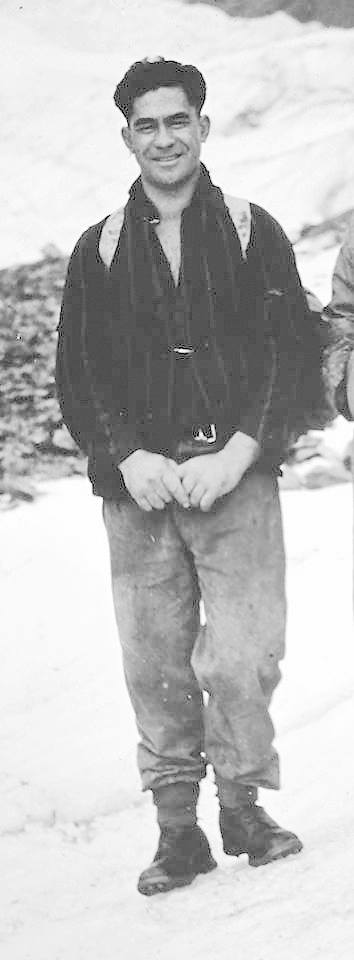

However, in the 1920s, Joseph (Hōhepa) Fluerty of Ngāi Tahu and Ngāti Māmoe decent, began his guiding career over Franz Josef Glacier / Kā Roimata a Hine Hukatere. The young man quickly became an expert mountaineer who was renowned for his masterful ability at step cutting ice.

Joseph Fluerty, Guide, Southern Alps.ca.1920. CREDIT: West Coast New Zealand History (Bob McKerrow)

As a guide, Hōhepa’s playful wairua delighted those wanting to explore the glaciers. Many of his manuhiri specifically requested for “the Māori guide Joe”, with one describing him as “full of mischief and as ready as an Irishman with his tongue”.

His comrades were often left in disbelief at Hōhepa’s masterful sense of direction. One story tells of him setting off from Franz Josef in the dark to find a lost party. After locating them without using a torch, Hōhepa placed glow-worms on his shoulder for the party to follow him back to safety.

The Living Māori Village Whakarewarewa

The first guides to Whakarewarewa Village were predominantly wāhine. The names of at least two wāhine toa stand out when referring to the foundations of this lucrative tourism adventure of Whakarewarewa - Mākereti Papakura (Guide Maggie) and Rangitīaria Dennan (Guide Rangi).

Under the wing of Guide Sophia, who took manuhiri on expeditions to the Pink and White Terraces prior to the Tarawera eruption in 1886, Guide Maggie learned to become an accomplished host, storyteller, and entertainer.

Guide Maggie gained international recognition when she hosted the duke and duchess of Cornwall and York at Whakarewarewa Village in 1901. She eventually became a popular subject for photographers, made numerous trips to Australia, wrote books on Māori culture as a means to gain economic benefits for her people and led a kapa haka to take part in international exhibitions in Sydney and England.

Mākereti Papakura. CREDIT: New Zealand History

Maggie’s work to promote the tradition of guiding and the arts and crafts of their people is revered through to the present day.

During her heyday, stories state that Guide Maggie was so famous that letters addressed to ‘Maggie, New Zealand’, would reach her.

Maggie’s thesis, The old-time Māori, was the first extensive published ethnographic work by a Māori scholar.

The stories associated with Guide Rangi also hold international revere. The young Māori woman guided many dignitaries through the Whakarewarewa Village.

During Eleanor Roosevelt’s 1943 tour, a photo of Guide Rangi welcoming Mrs. Roosevelt with a hongi caused a stir – the photo made international headlines with Pākēha claiming the welcome ‘audacious’ – it had broken Government protocol.

Guide Rangi broke another protocol during the Royal tour of 1953 after she led Queen Elizabeth II from the front. Royal etiquette states that no one must walk in front of the Queen, as a means of defining hierarchy.

During the tour, Guide Rangi also raised a supportive arm to the Queen while she was walking over a rocky surface. This caused quite a backlash. The Government slapped her with an official censure for being ‘too familiar’. This did not bother Guide Rangi, who noted that offering a supporting arm was better than the Queen slipping on the rocks.

Kāpiti Island Nature Reserve

Kāpiti Island Nature Tours was started in the late 1990s by John Barrett and his sister Amo Clark. While the business is 20 years old, the connection that John and Amo have to the island dates back more than 200 years.

Te Waewae Kāpiti o Tara rāua ko Rangitane (the official name of Kāpiti Island), has been an attractive island for many peoples who have resided on over the centuries. With its flourishing bird and marine life and strategic positioning, it was the perfect place for Ngāti Toarangatira chief Te Rauparaha and his allies to settle in 1824.

One of those allies was Te Rangihīroa, who is the tupuna, or ancestor, of John and Amo. He left the island under the protection of his daughter (and John’s kuia’s grandma) Metapere Waipunahau, when he went to fight in the Taranaki Land Wars in 1840.

Two generations later, and Metapere’s granddaughter, Utauta Parata (Webber) and her husband Hona became friends with a Captain Val Sanderson and his group. They spent many days and nights at the old homestead at Waiorua on Kāpiti Island discussing and plotting the original Forest & Bird Society.

The society was eventually formed in 1923. However, they became largely responsible for convincing the Government to pursue the acquisition of the remaining Māori land on the island.

Utauta and Hona vehemently opposed this and fought back against the Crown to ensure that what Māori land was left on Kāpiti Island remained in Māori hands.

Their fight was a success and, since then, whānau who live on the island have provided leadership and guidance on conservation projects.

These projects include the eradication of possums and rats in 1986 and 1996, and the establishment of the Kāpiti Marine Reserve in 1992.

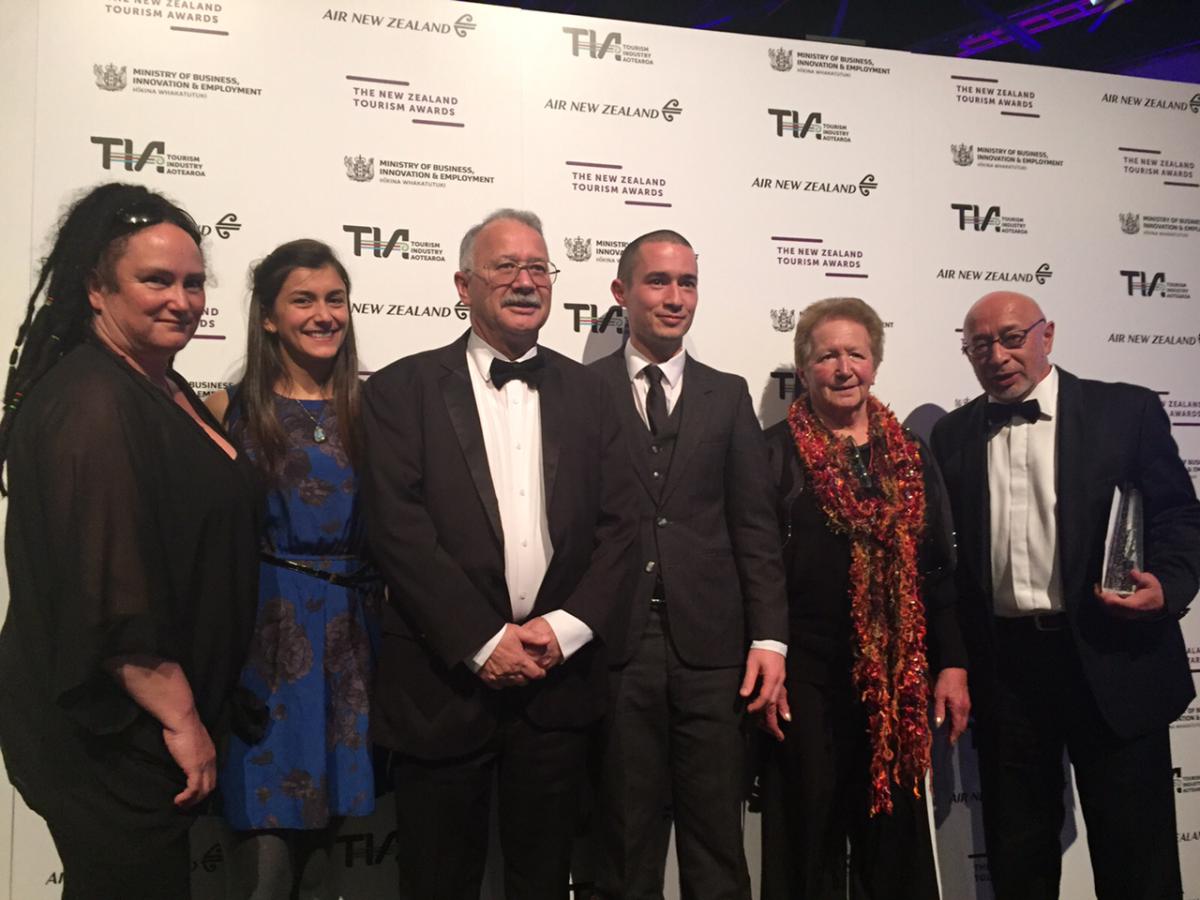

Kāpiti Island Nature Tours - the Barrett whānau at the Tourism New Zealand Awards in 2017.

Today, the kaupapa of the Barrett whanau’s tourism business provides manuhiri with an intimate interaction with a routinely inaccessible natural environment and some of our most treasured natural taonga.

For the whānau, it provides security and productivity for future generations. It allows the stories from the past generations to be passed down to the next, it teaches kaitiakitanga, and enhances the mana of the whānau, hapū, iwi and district of Kāpiti.

This is seen across the board in Māori tourism.

Cultural Wealth

Glaciers, geysers, and nature sanctuaries can be found in many places in the world, but it is our stories that define Aotearoa. Nowhere else can we experience these stories that have been passed down through generations of whānau lines.

These historical legacies are intergenerational legacies and taonga. When we invest in tourism, we invest not only in the economy, but also the cultural wealth of Aotearoa New Zealand.

From the STAPP recipients, 150,000 iwi descendants will continue to carry, partake in, and create tourism opportunities.

These businesses and their stories are so embedded in the community in which they exist, you’ll often find that Māori tourism businesses are providing kai to the homeless, local schools and kaumatua, or they’re running the local search and rescue and local volunteer fire brigades.

The investment from STAPP acknowledges these legacies.